Last month I had shared an article on Web Accessibility for Front-end Devs and another one sometime back on Mobile Accessibility. Last week Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2 was promoted to stable W3C Recommendation. Let’s see what’s new and what has changed.

One key point is that WCAG updates are intended to be backwards-compatible – by satisfying the requirements of WCAG 2.2, your site also satisfies the requirements of earlier versions of the specification. For this reason, the majority of WCAG 2.2 remains unchanged from WCAG 2.1.

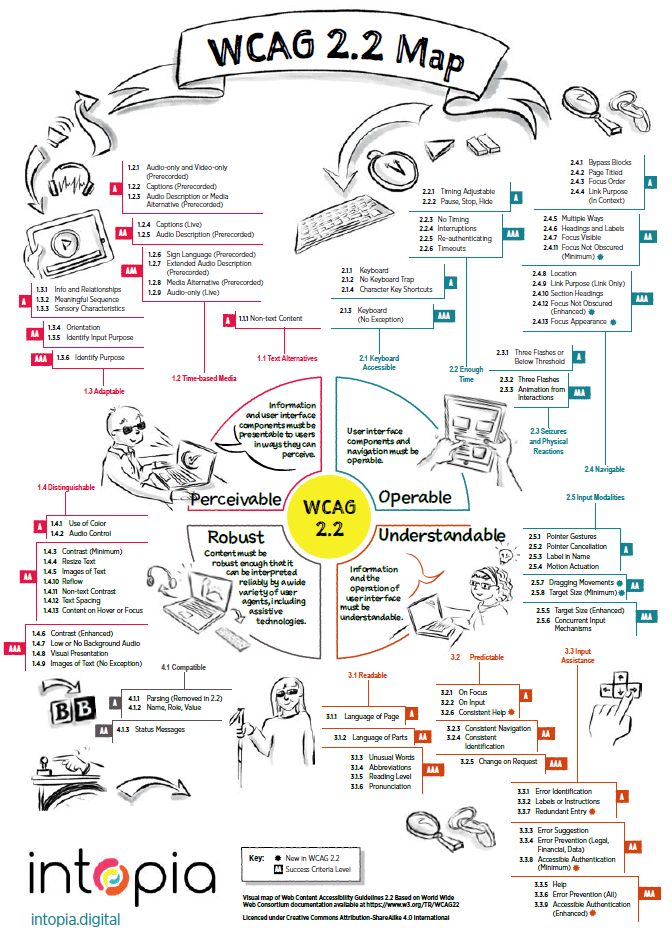

I came across Intopia’s cool map that covers the 9 new success criteria

One “breaking” change from WCAG 2.1 is the removal of Success Criterion 4.1.1 Parsing. This was useful when it was first introduced in WCAG 2.0 back in 2008, but thanks to changes in the HTML standard that specify a consistent way for browsers to error-correct malformed markup, it no longer provides any benefit to people with disabilities.

Beyond this change, WCAG 2.2 introduces 9 new Success Criteria, below are a few with details on how to meet the requirements:

3.3.8 Accessible Authentication (Minimum) (AA)

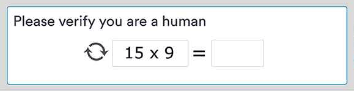

A cognitive function test (such as remembering a password or solving a puzzle) is not required for any step in an authentication process unless that step provides at least one of the following:

- Alternative: Another authentication method that does not rely on a cognitive function test.

- Mechanism: A mechanism is available to assist the user in completing the cognitive function test.

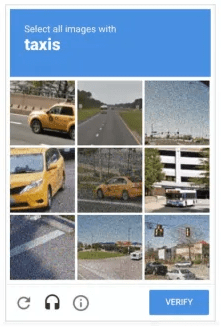

- Object Recognition: The cognitive function test is to recognize objects.

- Personal Content: The cognitive function test is to identify non-text content the user provided to the Web site.

How to meet the requirement

The simplest way to satisfy the criterion is not to have any cognitive function tests as part of an authentication process.

If the authentication process does have a cognitive function test, provide an alternative that does not rely on it – for instance, fingerprint authentication (via platform functionality like Windows Hello), open authorization (OAuth), use of a physical key/dongle, or app-based authentication (where a user opens a separate application and confirms that it is indeed them trying to log in).

Remembering and entering a username and password also falls under the definition of a “cognitive function test”. In these cases, the simplest way to meet the requirement is not to prevent copy/paste functionality on the login form fields, and allowing the use of password managers to autofill the fields, rather than having to manually type them in – this counts as a “mechanism”. The same is true for passcodes (such as TOTP codes): a user must be able to copy/paste these, rather than having to manually transcribe them.

This success criterion includes exemptions for “object recognition” – such as the classic “select all squares that contain a particular type of object” tests – and being able to recognise “personal content” – for instance, images that the user has previously uploaded to a site.

Note that this criterion (and its AAA counterpart) only apply to authentication – when a user logs into a site. They do not cover other situations where cognitive tests (such as CAPTCHAs) are presented to the user.

3.3.9 Accessible Authentication (Enhanced) (AAA)

A cognitive function test (such as remembering a password or solving a puzzle) is not required for any step in an authentication process unless that step provides at least one of the following:

- Alternative: Another authentication method that does not rely on a cognitive function test.

- Mechanism: A mechanism is available to assist the user in completing the cognitive function test.

This is the matching AAA version of the above 3.3.8 Accessible Authentication (Minimum). It is the same as its AA version, but without the exception for “object recognition” and “personal content”.

2.4.11 Focus Not Obscured (Minimum) (AA)

When a user interface component receives keyboard focus, the component is not entirely hidden due to author-created content.

Sighted people who can’t use a mouse need to see what has keyboard focus. Some web pages include content that is designed to “stick” to a specific area of the page, even when the page is scrolled, or otherwise overlap existing content. This includes sticky headers/footers, cookie banners, and floating sidebars and menus. This can lead to keyboard focus disappearing behind these elements, which is problematic.

How to meet the requirement

Ensure that when an item gets keyboard focus, the focus is at least partially visible.

2.4.12 Focus Not Obscured (Enhanced) (AAA)

When a user interface component receives keyboard focus, no part of the component is hidden by author-created content.

This success criterion is similar to its AA counterpart above, except that the entirety of the focus indicator must be unobscured, and there are no exceptions for configurable interfaces or the user’s ability to make focus visible again after opening additional content.

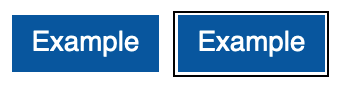

2.4.13 Focus Appearance (AAA)

When the keyboard focus indicator is visible, an area of the focus indicator meets all the following:

- is at least as large as the area of a 2 CSS pixel thick perimeter of the unfocused component or sub-component, and

- has a contrast ratio of at least 3:1 between the same pixels in the focused and unfocused states.

Exceptions:

- The focus indicator is determined by the user agent and cannot be adjusted by the author, or

- The focus indicator and the indicator’s background color are not modified by the author

How to meet the requirement

The simplest way to satisfy this requirement is to use an outline around the perimeter of a focused element that is at least 2 CSS pixels thick and has sufficient contrast (already covered by 1.4.11 Non-text Contrast).

2.5.7 Dragging Movements (AA)

All functionality that uses a dragging movement for operation can be achieved by a single pointer without dragging, unless dragging is essential or the functionality is determined by the user agent and not modified by the author.

How to meet the requirement

Make sure that there is a way for a mouse/touch user to still perform the same action using simple clicks/taps, rather than being forced to perform a dragging movement. For drag-and-drop interfaces, this could be achieved by allowing a user to click/tap on an item to “pick it up”, and a subsequent click/tap to “drop it”. For maps, add explicit directional buttons to pan the map view. For carousels, provide previous/next controls, or “dots” underneath the carousel to jump directly to a particular slide. For sliders, make sure that users can click/tap directly on the slider’s “track” to move the slider to that particular position.

3.2.6 Consistent Help (A)

If a Web page contains any of the following help mechanisms, and those mechanisms are repeated on multiple Web pages within a set of Web pages, they occur in the same order relative to other page content, unless a change is initiated by the user:

- Human contact details;

- Human contact mechanism;

- Self-help option;

- A fully automated contact mechanism.

How to meet the requirement

If your pages offer a help mechanism, make sure that the relative order of the help mechanism (or the link to reach said mechanism) is always in the same order relative to other page elements.

As WCAG 2.2 has been released as a stable W3C Recommendation, now is the time to familiarise yourself with the new success criteria, and to integrate them in your own accessibility and design considerations.

While you may find that you’re already compliant with some new criteria already, since they just enshrine best practices, others – such as 3.3.8 Accessible Authentication (Minimum) – may require more fundamental changes to existing processes and systems.

I definitely think that basing all design and development on WCAG 2.2 should now be the norm because I believe that each new version of WCAG offers a better experience for people with disabilities!